The execution of Kurdish political prisoners last week by the Iranian regime has sparked international outrage and a widespread strike by merchants in several Iranian cities. But according to inmates who were in the same prison and ward as Ramin Hosseinpanahi, Loghman Moradi and Zaniar Moradi, the three executed prisoners weren’t only deprived of their most basic judicial rights, but they were also deprived of the chance to say goodbye to their fellow inmates and families.

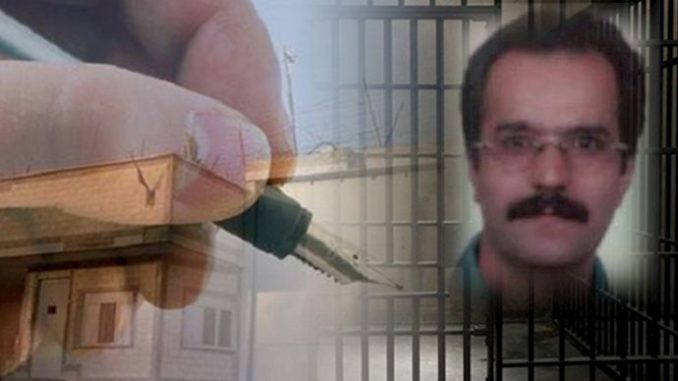

In an open letter that has been secretly sent out of prison, Iranian political prisoner Hassan Sadeghi, who shared a ward with Zaniar and Loghman in Iran’s Gohardasht Prison, has revealed damning details about the circumstances that the political prisoners were taken for execution, which are reminiscent of the violence and terror that has been plaguing the entire history of the mullahs’ regime.

Reiterating periods during which the Iranian regime carried out widespread executions of Iranian opposition members, Sadeghi, who has spent many years in the Iranian regime’s prisons, writes, “The summer of 1981 was ruthless, as so was the summer of 1988 and 2018.”

“In the September of 1981… we were 100 youths, aged 15-20, packed in a room where we shared our griefs and joys. Not a day went by without 10-15 people being executed. The names were called at around noon by the prison’s loudspeakers, which had become like a death knell,” writes Sadeghi. The prisoners then had about an hour’s time to pack their belongings and say farewell to their friends and fellow inmates. “They wouldn’t waste the hour they had, they would hug the other inmates and bid them farewell. When they were gone, we would wait to hear the sounds of gunshots, which indicated the end of the event. We would count the coup-de-grace shots (which specified how many prisoners had been executed).” The numbers sometimes amounted to 30 or 50 in a single day, Sadeghi recounts.

“In the September of 1988, a single question was asked and a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ determined the fate of the prisoner,” Sadeghi recounts, referring to the 1988 massacre, where the Iranian regime executed more than 30,000 political prisoners across the country in the span of a few months. Prisoners were asked whether they would repent their ties to and support for the Iranian opposition group People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK). If they didn’t, they would immediately be sent to the gallows.

Again, when the names were called, there was time to say farewell before the prisoners were taken away, Sadeghi writes, even though no one learned of their exact fate.

“But on September 5, this time in 2018, they didn’t even declare names,” Sadeghi says. “They said that the prison’s administration has summoned Zaniar, which was pretty common. Half-an-hour later, they called Loghman, which again was common. We thought they were taken to the administration to call their families.”

But an hour later, all the phones of the prison were cut off, Sadeghi recounts, and when the prisoners asked the guards, they were told that a utility vehicle had accidentally cut the telephone cables. “We started becoming worried about [Loghman and Zaniar],” Sadeghi writes.

“In 1981, they declared names and we knew what to anticipate. In 1988, they declared names and we knew what to anticipate,” Sadeghi writes. “But this time, we were left in the dark about what had happened to them. Why is the prison administration lying? Why aren’t the prisoners returning?”

Three days later, the prisoners of Gohardasht learned that their fellow inmates, Loghman and Zaniar Moradi had been executed, and they hadn’t even had the chance to say goodbye, Sadeghi says.

“In 40 years, this regime has set no limits to its crimes and it is filling the days and months with blood,” Sadeghi writes. “They died, but the memories of the blood-filled summers of Iran’s prisons will remain until and after the dawn of freedom sheds its light on my homeland.”

Source: PMOI/MEK