The Guardian, 11 August 2016 – The publication for the first time in Iran of an audio recording from nearly three decades ago has reopened old wounds from the darkest period in the Islamic Republic.

The Guardian, 11 August 2016 – The publication for the first time in Iran of an audio recording from nearly three decades ago has reopened old wounds from the darkest period in the Islamic Republic.

In the summer of 1988, thousands of supporters of the Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK) organization were executed in a massacre of political prisoners. In the pre-internet age, the incident was subject to a media blackout in Iran and received scant attention abroad, unlike other acts of carnage that rank alongside it, such as Srebrenica.

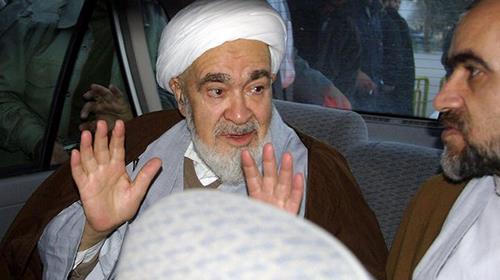

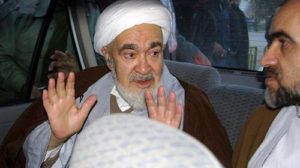

Only one senior Iranian official dared to speak out at the time: Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, who was in line to lead the country after Khomeini, then supreme leader and the leader of the 1979 Iranian revolution.

Montazeri wrote a number of letters to Khomeini condemning the executions, and the grand ayatollah soon fell out of favour. He was later placed under house arrest and faced huge restrictions until his death in December 2009.

This week, on the 28th anniversary of that bleak summer, Montazeri’s official website, run by his family and followers, published an audio file from a meeting he held in 1988 with senior judges and judiciary officials involved in the mass executions.

In an extraordinarily blunt manner, Montazeri is heard telling his audience, among them the sharia judge and public prosecutors, “In my view, the biggest crime in the Islamic Republic, for which the history will condemn us, has been committed at your hands, and they’ll write your names as criminals in the history.”

The 1988 mass execution is believed to have started after the MEK forces launched a military incursion against Iranian forces

In the audio recording, Montazeri tells his audience that he believes the authorities had a plan to execute political prisoners for a few years and found a good excuse in the wake of the incursion.

The ayatollah says he felt compelled to speak out because otherwise he would not have an answer on the “judgment day”. “I haven’t been able to sleep and every night it occupies my mind for two to three hours … what do you have to tell to the families?”

Later in the recording, Montazeri insinuates that the number of people executed since the revolution outnumbered those put to death by the deposed Shah. When an official seeks his consent for the last group of around 200 people to be executed, he is heard saying fiercely: “I don’t give permission at all. I am opposed even to a single person being executed.”

Although execution of dissidents was rife in Iran in the 1980s, the 1988 summer executions were on a different scale. Amnesty International estimates the number of people put to death in that summer alone to be about 4,500, although others talk of bigger numbers.

A fatwa issued by Khomeini in 1988 ordered the execution of apostates who refused to recant. Thousands of prisoners were brought before committees and asked whether they renounced their political affiliation, if they were Muslims, whether they prayed and if they believed in the Islamic Republic. Some were also asked if they were prepared to walk through Iraqi minefields, according to the audio file.

Those who gave a negative answer in questioning that lasted a few minutes were put to death. Many were buried in a piece of unmarked land in the Khavaran cemetery near Tehran. Every year, as families gather to commemorate the deaths, riot police block their way.

The emergence of the audio file has revived calls for an inquiry into the executions. Over the past 28 years, survivors and families of the victims have tried to support each other. In January, an Iranian woman who lost five children and one son-in-law in executions in the 1980s – Nayereh Jalali Mohajer, known as “Mother Behkish” – died.

Sahar Mohammadi, who lost his parents and two uncles, told the Guardian: “There’s no other way than this massacre to be investigated and perpetrators brought to justice in a fair, real trial.”

Mehdi Aslani, a survivor who spent five years in jail, likened the emergence of the audio file to finding the black box of a plane that has crashed: “We know what has happened but we’re hearing the last words of the pilot.” Aslani said he shared a cell with a dozen others who were put to death, including Jahanbakhsh Sarkhosh, who was executed despite nearing the end of his jail sentence – “only seven months were left”, he said. Another victim, Jalil Shahbazi, took his own life after coming under a great deal of pressure from the death committee.