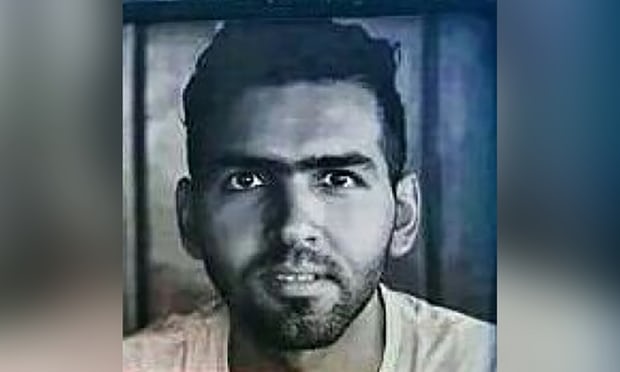

Amir Taghinia flew to British Columbia last week, thanks to a group of private sponsors, after nearly four years on Manus

A refugee who was detained on Manus Island has left to begin a new life in Canada, through a group of private citizens who sponsored his freedom.

Amir Taghinia, a refugee from Iran, flew to Coquitlam, British Columbia last week, after nearly four years on Manus Island.

“To be honest, I cannot believe I am in Canada, I am so thankful,” Taghinia told the Guardian. “But I cannot forget about my friends, they are starving, they have no water to drink. It is very, very likely we will have more deaths in the next coming days.”

Taghinia said he was overwhelmingly grateful to the Canadians who had worked together to find him a path to freedom. He is living at the house of Wayne and Linda Taylor after their daughter, Chelsea, met him in 2015 while she was administering immunisations to Manus Island detainees.

“I really respect these people, I now consider them as part of my family. I am seeing the generosity Canadians have towards human beings. But look what is happening to Australia: Australia’s reputation is being ruined by what the Australian government is doing to people.

“Here, when people hear I am a refugee they are so happy to help me, to assist me in any way they can. On Manus Island, the Australian guards, they hate me because I am a refugee They call me by my boat number – EDE039. But here they call me my name, they respect me as a human being. I am glad to call myself Canadian.”

The realisation of a private sponsorship from Canada, from a group of a dozen residents in Coquitlam, comes as the stand-off on Manus Island worsens and the men still inside the centre run out of food and water.

Australia has again rejected New Zealand’s standing offer to accept 150 refugees from its offshore detention islands, and progress on the vaunted US resettlement deal, which has taken 54 refugees so far, has ground to a near standstill.

Taghinia was formally recognised as a refugee on Manus Island: that is, authorities judged he had a “well-founded fear of persecution” in Iran and could not legally be returned there. “I was hostage there,” he told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. “If the Canadian government and my sponsors weren’t there, I may have died on this island.”

Taghinia was outspoken in his criticism of conditions in the Australian-run detention centre during his time on the island.

“I couldn’t sit silent,” he told CBC. “The [camp administration] intelligence report, they called me the agitator of the centre and a trouble-maker. I was not making any trouble. I was just defending human rights.”

For more than 30 years, private sponsorship of refugees – by families, private citizens, religious, and community groups – has been a feature of Canada’s refugee resettlement effort. Refugees who are privately sponsored are in addition to those resettled by the government.

Since the late 1970s, more than 280,000 have been resettled in Canada by private sponsors, who commit the equivalent of one year of social security – about $30,000 – in cash or by in-kind commitment of housing, clothing, furniture and food, to assist a refugee family of five to settle into the country.

Australia has a pilot private resettlement program, with up to 1,000 places this year. But the cost is prohibitively high – up to $55,000 for a family of five, to which the government plans to add an “assurance of support” of $30,000 to $60,000 – and each refugee resettled privately is offset against the number resettled through the government’s program.

There have been calls from Liberal, National, and Labor parliamentarians to boost Australia’s private sponsorship program to as high as 10,000 annually.

“I will be relieved when every single person on Manus and Nauru are in a safe place. Australia has completely withdrawn from the centre, they have dumped these people there in the hands of nobody,” Taghinia said.

Tim O’Connor from the Refugee Council of Australia said the Australian government was threatening the lives of hundreds of innocent people through its inaction, while governments and communities elsewhere in the world were “bending over backwards to provide solutions”.

“The Australian prime minister is saying: ‘We don’t want these refugees, but you can’t have them either,’” he said. “It’s an absolutely bizarre situation Prime Minister Turnbull has got himself into. New Zealand is prepared to take Australia’s refugees from Manus, caring members of the Australian community are putting their hand up, even people in Canada have gone to great lengths to ensure they safety of people whose lives are in jeopardy. Prime Minister Turnbull should be putting human lives in front of short-term political point-scoring.”

As Taghinia restarts his life after four years in offshore detention, the refugees and asylum seekers who remain in the Manus Island detention centre are continuing to defy instructions to leave, saying they are not safe in the Manusian community, and that they have been abandoned by the Australian government – which has legal responsibility for them. Tensions between the transplanted refugee and asylum seeker population and local Manusians have been growing over recent months, as evidenced by a series of violent incidents.

Many Manusians in the conservative, familial Lorengau community are sympathetic towards the refugees’ situation, but argue there are not the resources or space in the small town, built on close-knit clanship links, to support a new community.

The 600 men still in the detention centre are living without electricity, running water, and dwindling supplies of food and medicine. The detention centre sits within a military base. Civilians, having briefly had access, have been banned from visiting because, it is believed, they will bring in food and medicine.

A small amount of food was brought into the centre Monday night, the Guardian has been told. But navy personnel are blocking access to the detention centre from outside and preventing food being brought in.

“We are in a critical situation,” refugee Behrouz Boochani told the Guardian from inside the centre. “Starvation is the reality of the Manus camp and for hundreds of people, their bodies are getting weak. We have been deprived from having access to food on the past six days – we have saved a little bit of food to survive. We rationed a little food the past week and now that I’m writing, there is no food here. Police and navy have been ordered to prevent food into the prison camp. We no have access to food.”

The UN has urged Australia to feed and protect the men, describing the situation as an “unfolding humanitarian emergency”.

“We call on the Australian government … who interned the men in the first place, to immediately provide protection, food, water and other basic services,” said Rupert Colville, a spokesperson for the UN high commissioner for human rights.

But PNG authorities are urging the men to abandon their protest and accept temporary resettlement elsewhere on the island.

Petrus Thomas, the PNG minister for immigration and border security, said the detention centre site at Lombrum had been decommissioned, and services could not be restored there.

“All necessary equipment and structures for the provision of services have been removed and it is no longer possible to restore any services. Decommissioning activities have been extensive. The absence of services should not come as a surprise to anyone.”

Thomas said the PNG government was trying to work cooperatively with refugees and non-refugees to ensure they had access to necessary services.

“Those observers including international organisations who claim to have the interests of the refugees and non-refugees, I implore you to desist from influencing the residents to remain at Lombrum … and to encourage these individuals to avail themselves of the new facilities.”

There is a growing sense in PNG that the refugees and asylum seekers have been abandoned by Australia, and left for PNG to deal with. The PNG government warned last week that those held on the island remained Australia’s legal and financial responsibility.

PNG lawyer Ben Lomai, and Australian barrister Greg Barns have launched a supreme court action seeking orders that essential services be immediately restored to the detention centre to protect the former detainees’ constitutionally-guaranteed human rights. The supreme court last year ruled the Manus detention was “illegal and unconstitutional”.

Elaine Pearson, the Australian director of Human Rights Watch, said the safety of refugees and asylum seekers could not be assured in the Lorengau, to where they are being encouraged to move.

“Refugees and asylum seekers have been repeatedly robbed and assaulted in Lorengau town, with little action taken by police. There has been an escalation in violent assaults in recent months, three attacks since June required medical evacuations to Port Moresby or Australia due to inadequate medical care on the island.

“Refugees and asylum seekers don’t need a transfer to a different facility on Manus where they will remain vulnerable to violence. They need a lasting solution, and it’s up to Australia to provide that for them without delay.”